By Carl Graves, with Paul Walters/photos as noted

By Carl Graves, with Paul Walters/photos as noted

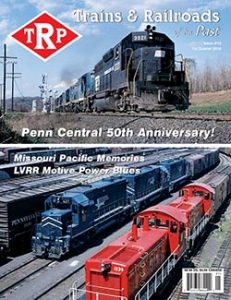

Although the Missouri Pacific was never a high priority for us, we managed to photograph, either together or separately, operations of this railroad in six of the nine states in which it had a major presence before or within a few years after its merger with the Union Pacific in late 1982. (The MP also had a few track miles in two other states, Tennessee and Mississippi, thanks to Mississippi River bridges to Memphis and Natchez, respectively.)

We feel fortunate to have captured enough MoPac images in rural and urban areas, on its own rails or on adjacent lines, to create a modest set of photographs and memories of this big blue transportation company, which now has been a fallen flag for over three decades. We’ve also added a few classic images to the article for perspective, as well as some photos of blue diesels after the MP merger.

Here’s a MoPac freight with a classic motive power consist right out of the past with high-nose GP7 no. 1721 leading three GP18’s beneath a cantilever signal bridge in March 1980 at Malvern, Ark., which is southwest of Little Rock on the busy line to Texarkana. Photo by Paul Walters

Corporate Overview

The Missouri Pacific had experienced many years of hard times in the twentieth century, but by the time we started aiming our cameras at it in the early 1970s, the railroad had recovered and was prosperous. After declaring bankruptcy in 1933 during the Great Depression, the MoPac was in receivership for 23 years. In 1956 the reorganized railroad started a 26-year period of reconstruction of both its physical plant and finances. For example, the railroad opened the massive two-hump Neff classification yard in Kansas City, Mo., in 1959 and a single hump yard in North Little Rock, Ark., two years later.

One company officer responsible for the reconstruction was Downing Jenks, who became MP president in 1961 and later chairman of the board. He took steps to improve track and roadbed, freight car maintenance and its locomotive fleet, as well as information technology.

Missouri Pacific Alco RS3 no. 1065 is reflected in an ocean-sized puddle at Dolton, Ill., on July 5, 1971. Between 1964 and 1976, MP replaced the Alco prime movers in its fleet of RS3s with EMD 567s, reclassifying the units as “GP12.” Note the triple exhaust stack manifold as part of the conversion. Photo courtesy Kevin Idarius, from the collection of Louis Marre.

In contrast to some other railroads, the MoPac experienced good times in the 1970s. Despite “stagflation” that hampered many U.S. industries and railroad lines, the Missouri Pacific’s revenue and income rose nearly every year in this decade. It purchased new and used locomotives in the 70’s, and then in October 1976, the Texas & Pacific Ry. and the Chicago & Eastern Illinois RR were officially merged into the MP. A company map in a 1975 Official Railway Guide proudly referred to the railroad as the “Route of the Eagles” with “More than 11,000 miles… serving the West-Southwest Empire.”

Although we were unaware of its strong balance sheets, the company’s prosperity did affect our view of its lines. While we saw rails and rolling stock of railroads like the Rock Island fall apart, the MP property and trains we encountered were for the most part in good shape. The “Jenks blue” paint scheme, which reminded us of a corporate executive’s suit color, was not as photogenic as Union Pacific Armour yellow or the Santa Fe’s bright yellow and blue, but at least most MoPac engines were clean and not faded, in contrast to many Rock Island and Missouri-Kansas-Texas locomotives.

A southbound MP-powered Union Pacific freight on the UP’s Coffeyville Sub (former MoPac Kansas City Sub) is south of Kansas City in the fall 1984, perhaps going under the Metcalf Road overpass. A line relocation that occurred since I took these pictures makes the exact location difficult to pinpoint. Photo by Carl Graves

In the mid-70s we did not realize that the MoPac’s days were numbered. The 1980 Staggers Act that partly deregulated the nation’s freight railroads also stimulated a wave of mergers. On December 22, 1982, the Missouri Pacific merged with the Union Pacific, which also acquired the Western Pacific. According to railroad historian David C. Lester, “Despite an initial announcement that the Missouri Pacific would be a ‘sister’ railroad to the Union Pacific and would maintain its own identity, the Missouri Pacific name all but disappeared from the scene within a few years.”

The company’s headquarters were in St. Louis in a stout high-rise that looked, with faded white facade and overbearing cornices, like part of the old Bell System. My friend Paul worked in St. Louis for several years after the UP takeover, and often walked past the building on his way to lunch. He would sometimes stop and chat with railroad employees, many of whom had worked originally for the MoPac, and they all mourned the fallen flag. We continued to photograph Missouri Pacific diesels for six years after the merger. “Jenks Blue” continued to ride the rails because in December 1982, the MoPac actually had more route miles and locomotives than the UP, and the operating department of the two roads did not merge until January 1986. Although our photographic efforts were limited, given the size of the MoPac at the time of the UP takeover (11,167 route miles), some of our best pictures came in the years 1983-1988, when remnants of this once mighty blue empire were still visible.

A pair of MoPac GP7’s bracketing two GP9’s are rolling high above the city of St. Louis, Missouri. Take note that one of the tank cars on ground level is lettered “Eastman…” it could be carrying chemicals for developing this very roll of film! Photo by Jim Boyd, collection of Kevin EuDaly

Train Frequency and Symbols

Although we did not keep records in the 1970s and 80s, our memories of MoPac train volume was light to moderate on the routes we visited. Based on our experiences, we estimate that the 24-hour train counts on most subdivisions were in the teens or single digits. The Omaha and Oklahoma Subs each saw four trains on average in 24 hours, while the Carthage, Osawatomie, and Van Buren Subs ran perhaps eight trains or less in the same time period. The Coffeyville Sub, as well as the River and Sedalia Subs west of their junction near Jefferson City, each had maybe 14-16 per day, with the Gorham Sub and the Kansas City Sub seeing 20 or more in that same time period.

Like other railroads, MP traffic varied, sometimes significantly, from day to day. A careful observer of the Carthage and Cotter Subs in the late 70s and early 80s said that on a good day, he might see 7 trains in daylight, while on a bad day, he would see none! Other stretches of the system (Jefferson City to St. Louis as well as St. Louis to Little Rock) were busier, but for various reasons we did not visit them…

The caboose of a southbound Missouri Pacific loaded coal train passes Burlington Northern SD40-2 no. 7803, the lead unit of a northbound coal empty at Lenapah, Okla., on the Wagoner Sub July 1981. Photo by Paul Walters